Ideally, an asset allocation for taking RMDs should be able to generate high enough earnings to satisfy IRS required withdrawals without eating away at the initial investment. This calculates to be at least 3.7% in combined dividends and/or interest. If your interest and dividend income aren’t sufficient enough to cover RMDs, then the distributions will most likely have to come from principal. Why is that so bad? Well, with average life expectancy rates today higher than they’ve ever been, most people need to plan for 30 years of retirement. That being the case, spending any principal at all, especially during the early years of retirement, can negatively impact all of the remaining years.

A better understanding of this can come from looking at what we know about a 30-year mortgage. When you first start making payments, you’re not paying back much principal at all. Instead, you’re paying primary interest and just a small amount of principal. But, as the years go on and the balance gets paid down, you pay a little less interest and a little more principal. The process continues until, after 30 years, your mortgage is thankfully paid off. But, consider the process in reverse. Take a pool of savings worth $1M, generating 5 percent interest per year — i.e. $50,000. If you take even a little bit more than that $50,000 each year, just a small amount of the principal, that sum will be depleted within 30 years in much the same way a mortgage is paid off.

Today’s Challenges

So, you want to avoid having to use any principal to cover your RMDs, but it’s important here to distinguish principal from capital gains or capital appreciation because those are things you can’t always depend on. Sometimes, when you invest for appreciation, you end up getting depreciation instead; you count on growth but end up getting shrinkage.3

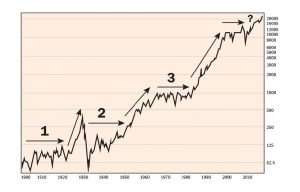

Admittedly, this was less of a danger many years ago. During the 1980s and 1990s, in the midst of the best long-term secular bull market in U.S. history, investors could have conceivably satisfied their RMDs completely from capital gains, rather than dividends, without encroaching on principal. But since the year 2000, the opposite has been true. Since then, the market has seen two major drops (of nearly 50% from 2000–2002 and nearly 60% from 2007–2009), and, according to what I believe are the lessons of market history, another major drop is a possibility within the next 10 years.

Unfortunately, it’s also true that in today’s market, it’s not easy to generate the kind of interest or dividends you need to satisfy RMDs without touching principal. Interest rates in money markets are well below 3.7 percent, and even bond mutual funds aren’t generating enough, once you factor in management fees. What’s more is that bond mutual funds can also be tricky because, unlike individual bonds, they don’t give you a fixed interest rate or fixed maturity date that guarantees the return of their face value, assuming there have been no defaults. When something happens in the bond market that causes bond values to drop, a portfolio of individually held bonds and a portfolio of bond mutual funds might drop similarly in value, but for the individual bond holder, it’s ultimately only a temporary paper loss, as they will get 100% of their money back at maturity as long as they do not sell and there are no defaults. Not so for the bond fund holder as bond funds never mature.

Reverse Dollar-Cost Averaging

Still, any of those options may be preferable to a diversified stock portfolio or stock mutual fund portfolio if the dividend you’re earning there is less than 3.7 percent annually (which it likely is), and you end up selling core shares each year to satisfy your RMDs. This is actually one of the most com- mon and potentially disastrous financial mistakes made by retirees: the error of reverse dollar-cost averaging.

Most people know what dollar-cost averaging is and have wisely used it in the course of saving over the years, typically by investing in a 401(k). The purpose of dollar-cost averaging is to get your average cost or purchase price down to help you buy low and sell high, which is the cornerstone principle of smart investing.

So, if you were to set out to buy $100 per month of a mutual fund and the first month the fund was worth $10 a share, you would buy ten shares. But, what if the unthinkable happened and in the second month, the fund dropped to $5 a share? Well, if you stuck with your plan, you’d have to buy 20 shares to get $100 worth. So, after two months, your average cost per share would seem to be $7.50, but in actuality, it would be lower: $6.66. That’s because you bought twice as many shares at $5, and half as many shares at $10. Dollar-cost averaging helps you get your average costs down. 4

The problem, however, is that once you’re at a point where you’re not saving into your fund, and you’re drawing from it in order to satisfy RMDs, the same principles apply but in the opposite direction. You start reverse dollar-cost averaging.

Taking the same example, let’s say that the first month, you liquidate $100 and you sell 10 shares, and the second month, the unthinkable happens and the fund drops in half. Now, to withdraw your $100, you have to sell twice as many shares, therefore you sell 20 shares. So, now what’s your average sales price per share? Again, the math is the same: now, instead of taking your purchase price down from $7.50 to $6.66, you’ve taken your sales price and pushed it down. You’ve been forced by the IRS to sell low.

Radical Question

So, while dollar-cost averaging is a great strategy for saving, reverse dollar-cost averaging is one of the most cancerous strategies you could embark upon. This goes back to the original point: if you’re going to have money in the stock market in your IRA during retirement, you want to make sure that you’re earning enough interest or dividends on that money to satisfy your RMDs. Once again, though, that’s a major challenge in today’s market — such a challenge in fact that it begs the question: should you have any money at all in the stock market — in your IRA, 403(b), 401(k) or 457 plans — once you’ve retired?

That may seem like a radical question based on what “the professionals” and textbooks have always said: “Everyone needs to have some money in the stock market as a hedge against inflation.” The unfortunate reality is that the stock market has never really been, on average, a very reliable inflation hedge. In the course of stock market history, there have been long periods when it’s been a decent inflation hedge but even longer periods when it hasn’t. Historically speaking, there are certain periods when an IRA holder can, indeed, stay invested in the stock market and take his RMDs from fairly predictable gains and capital appreciation, but there are also times where those RMDs have to come out of principal because there are net gains in the market — or even losses.

DOW JONES INDUSTRIAL AVERAGE 1900-2020

As the chart above shows, these periods seem to have recurred throughout history – so much so that they need to be understood and considered as part of the process for determining whether your allocations are right and sufficient for RMDs.

Getting started is as easy as contacting a qualified financial advisor who specializes in the universe of non-stock market, income-generating alternatives. These are all conservative or moderately conservative instruments designed to generate consistent income through interest and dividends — generally in the 3 to 5 percent range — and with substantially less risk than aggressive, market-based approaches like common stocks, stock mutual funds, and speculative real estate investments. This is income that can provide cash flow for your retirement or that can be reinvested to obtain growth organically, or “the old-fashioned way.”