Retirement income for any purpose, whether it be living expenses, major purchases, or satisfying RMDs, should ideally come from interest and dividends on your savings and investment vehicles, not from principal. The same concept applies when talking about maximizing Social Security.

Spending down on principal in retirement has never been a good strategy, but today it’s more of a “slippery slope” than ever before, especially in the early years of retirement. Again, that’s because average life expectancy rates today are higher than they’ve ever been, and most people need to plan for 30 years of retirement. To see the potential danger there, consider a 30-year retirement like a 30-year mortgage in reverse.

When you first start making mortgage payments, you’re not paying back much principal at all. Instead, you’re paying primary interest and just a small amount of principal. But, as the years go on and the balance gets paid down, you pay a little less interest and a little more principal. The process continues until, after 30 years, your mortgage is thankfully paid off. Now, imagine the process in re-verse. Take a pool of savings worth $1M, generating 5 percent interest per year – i.e. $50,000. If you take even a little bit more than that $50,000 each year, just a small amount of the principal, that sum will be depleted within 30 years in much the same way that a mortgage is paid off.

Your Options

So with that in mind, what are some of your savings and investment options today for generating income through interest and dividends to supplement Social Security? Well, there is the bank of course, but with bank accounts and certificates of deposit earning around 2 percent annual interest at best right now, that doesn’t make for a very substantial income source.* Even with $1 million in the bank, 2 percent translates into just $20,000 a year. (And if you’re thinking short-term interest rates have to start coming up soon, that’s not necessarily the case. Keep in mind that Japan has been in a near-zero interest rate environment for over 20 years now).

* Source: Bankrate.com3

So, if banks and money markets aren’t a good practical option right now, even if you have $1 million, what about stock dividends? Unfortunately, the math is very similar. Even if you have $1 million in a stock or stock mutual fund portfolio today, with an average dividend of just 2 percent, you’re still getting only $20,000 in annual income if you don’t want to touch the principal – which can be an especially slippery and potentially dangerous slope when it comes to stocks.

To help me explain that further, let’s consider another scenario. Let’s say you’ve decided to delay taking your Social Security benefits until age 70 in order to receive a higher amount, but you decide you’re still going to retire at age 62. In this case, you not only have to consider how best to supplement your Social Security income once it kicks in, but you have to determine how you’re going to fill that eight-year “income gap” until it does kick in once you’ve stopped working.

If you decide to leave your $1 million in the bank at 2 percent interest, odds are you’d have to spend at least an additional $20,000 annually from the principal over the course of those eight years to make ends meet, dropping your nest egg down to $840,000. Taking it a step further, you could decide to leave your $1M under a mattress earning 0 percent interest, in which case it would be worth $680,000 by the time you were 70, assuming a $40,000 withdrawal per year for eight years.

But, now let’s say you decide to leave your $1 million in stocks or stock mutual funds for those eight years and another major market drop occurs similar to the two that have taken place since the year 2000. The first time, from 2000 to 2002, the market took nearly a 50% drop and it took more than seven years to get back to its previous high. Then from 2007 to 2009, the market took almost a 60% drop and took just under seven years to recover. If you’re a 62-year-old retiree taking assets for eight years and you happen to get caught in the next seven-year downdraft, it means that each year the market drops, you’ll end up selling more shares of your stock or stock mutual fund to get your same withdrawal. That means that even when the market comes back within seven years or so, by the time you hit age 70, you still will not have even have come close to getting all of your money back. You might, in fact, have only between $300,000 or $400,000 left at the end of the eight-year period, and you will have ultimately cannibalized your nest egg worse than if you had put it in the bank or under the mattress.

‘Cancerous’ Strategy

This kind of “cannibalizing” of principal is actually a common mistake that retirees and people close to retirement make: the error of reverse dollar-cost averaging. Most people know what dollar-cost averaging is, and have wisely used it in the course of saving over the years, typically by investing in a 401(k). The purpose of dollar-cost averaging is to get your average cost or purchase price down to help you buy low and sell high, which is the cornerstone principle of smart investing. 4

So, if you were to set out to buy $100 per month of a mutual fund, and the first month, the fund was worth $10 a share, you would buy ten shares. But, what if the unthinkable happened in the second month, and the fund dropped to $5 a share? Well, if you stuck with your plan, you’d have to buy 20 shares to get $100 worth. So, after two months, your average cost per share would seem to be $7.50, but in actuality, it would be lower: $6.66. That’s because you bought twice as many shares at $5, and half as many shares at $10. Dollar-cost averaging helps you get your average costs down.

The problem, however, is that once you’re at a point where you’re not saving into your fund, and you’re drawing from it to supplement or fill a gap with your Social Security income, the same principles apply but in the opposite direction. You start reverse dollar-cost averaging.

Taking the same example, let’s say that the first month, you liquidate $100 and you sell 10 shares, and the second month, the unthinkable happens and the fund drops in half. Now, to withdraw your $100, you have to sell twice as many shares, therefore you sell 20 shares. So, now what’s your average sales price per share? Again, the math is the same: now, instead of taking your purchase price down from $7.50 to $6.66, you’ve taken your sales price and pushed it down. You’ve been forced by the need for income to sell low.

Dollar-cost averaging is one of those things that works great in one direction and is horrible in the opposite direction. Whereas dollar-cost averaging is a great strategy for young savers, reverse dollar-cost averaging is one of the most cancerous strategies you can embark upon. If a 2% dividend doesn’t yield enough income to supplement your Social Security or allow you to fill an income gap, then you may need to question whether you should have a significant allocation in the stock market during retirement. In fact, because it’s so difficult today to earn any reasonable amount of dividend on an average stock portfolio, you may want to take it a step further and consider the question: should you have any money in the stock market at all once you’ve retired?

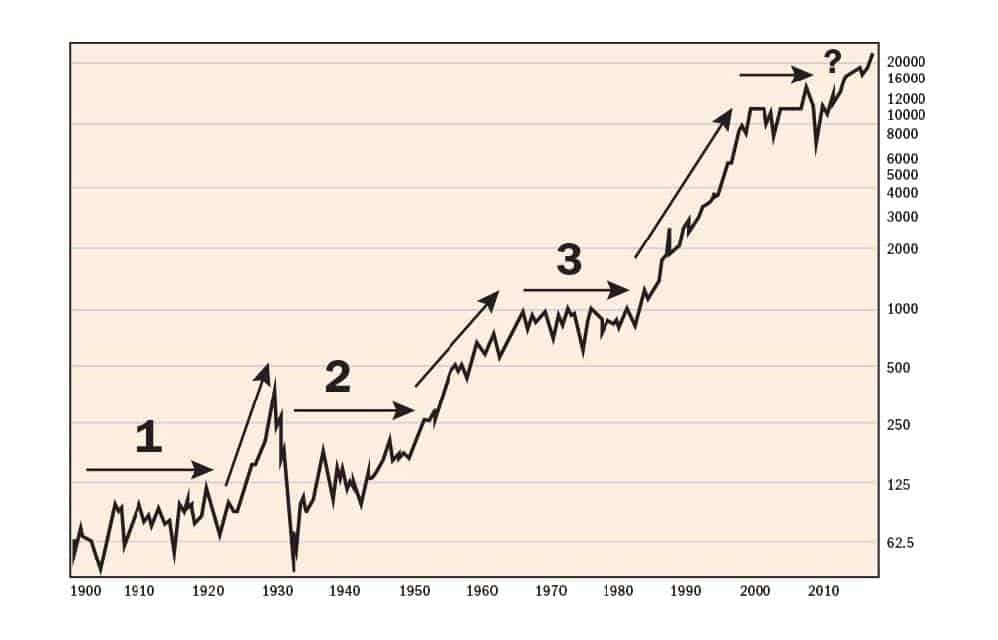

That may seem like a radical question based on what “the professionals” and textbooks have typically said: “Everyone needs to have some money in the stock market as a hedge against inflation.” The unfortunate reality is that the stock market has never really been, on average, a very reliable inflation hedge. In the course of stock market history, there have been long periods when it’s been a decent inflation hedge but even longer periods when it hasn’t. Historically speaking, there are certain periods when an investor can, indeed, stay invested in the stock market and generate income from fairly consistent gains and capital appreciation, but there are also times when that income has to come out of principal because there are no net gains in the market – or even losses.

Universe of Income-Generating Options

As the chart on the next page shows, these periods have sometimes been repeatable throughout history – so much so that they need to be understood and considered as part of the process for 5

determining whether your allocations are right for maximizing your Social Security benefits.

Getting started is as easy as contacting a qualified financial advisor who specializes in the universe of non-stock market, income-generating investments. Many people lost sight of this universe during the ‘80s and ‘90s, the best U.S. stock market in history.

There are conservative or moderately conservative investments designed to generate consistent income through interest and dividends – generally in the 3 to 5 percent range – and with substantially less risk than aggressive, market-based approaches like common stocks, stock mutual funds, and speculative real estate investments. This is income that can provide cash flow for your retirement or that can be reinvested to obtain growth organically, or, as I like to say, “the old-fashioned way.”